Hey everyone. This week, I’m discussing the great retrospective on Marisol at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts that just ended. Marisol is a Venezuelan-American artist who has recently seen renewed interest once again. I was lucky enough to catch it last month.

Also, in anticipation of his new album dropping next week, there’s a little review of Helado Negro’s 2019 album This is How You Smile. I haven’t written about music in a bit; post-university burnout ensured that. But we out here once again.

Huge thanks to everyone who’s subscribed so far. Leave a comment to let me know what you think this week. Tell your friends. Consider donating for access to more stuff. :* - Nate.

Marisol

My mom didn’t talk about Venezuela growing up. My only points of reference were it being the punchline for a throwaway joke in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, references in Grand Theft Auto, and the stories my dad would tell me about his encounters with guerillas and federal police. I only learned what my abuelo’s name is this past month. Shoutout Omar.

For a lot of folks, growing up biracial means you’re put on one side when it’s most convenient for the people around you. In school, I was the only kid from an immigrant household, so I was appointed as consultant for anything South American. These days, I just make arepas and speak fluent Spanglish. I make an effort to do stuff for the culture now and again. Last week, I returned to the MMFA to check out the Marisol exhibition. It was either that or spoken-word poetry.

Marisol: A Retrospective is precisely as it sounds. After walking up the steps, onlookers are met with a brief introduction to her work via one of those large, drywall slabs with text printed overtop. The French and English blurbs are identical in size. This is a feat of graphic design. I spent a good few minutes looking at the line and letter spacing under the guise of being a slow reader. Decked out in muted pastels, the informational material scattered throughout the exhibition mimics the aesthetics of the pop art movement in which Marisol was a key figure.

Born in 1930, Marisol Escobar was a Venezuelan-American artist whose work spanned various forms and subject matter. She’s known best for her deliberately crude wooden sculptures, criticizing notions of female beauty in post-war American contexts. Growing up between Caracas and New York, Marisol was a deeply religious child, scarred by the suicide of her mother. After prolonged silences and boarding school expulsions, she began her formal art education at Otis Art Institute in LA.

She hit her stride after subscribing to the pop art movement, using found materials and gleaned wood to build sculptures to comment upon the emergence of the nuclear family and conservative values post-war. The figures in her work are crude sculptures, middle-class workers and artists who share the same construction as their environment. The Jazz Wall (1962) sees this, with its group of hombres seemingly cut out of the wall behind them. They all hold real instruments, possibly sourced from the trash, with blank expressions or that weird focus you get while improvising. For Marisol, place and the self are the same. Wood is an organic material, as are we. It can either be built up or torn down, shaped in whichever way is deemed correct by popular thought.

The women in Marisol’s work are often blocky, modular-looking figures whose stereotypically feminine features clash with their cubed torsos. Breasts, legs, and immaculately painted faces break from their literal molds, showing women as both a constructed entity and objectified idea. Sometimes, they’re just a block. They’re solid and blank-faced, standing roughly 6 feet tall. Their faces are taken from molds of Marisol’s face, layered over each other or side-by-side. “That two faced-bitch,” a kid near me said, probably dragged along by her parents as the rest of Montreal’s ran free during the month-long teacher’s strike. On some sculptures, only a photo suffices for a mug. One of them even has a dog with a taxidermied head. Some dogs are equally unnatural if you think about it hard enough.

Other rooms in the gallery touch upon Marisol’s personal fascinations and specific interests. Sculptures and photographs of marine life encircle the room, something she loved before seeing coral reefs literally waste away in the 70s. The next holds sculptures of political figures Marisol thought important or stupid enough to immortalize as stocky totems. Marisol’s entire career is touched upon in the half-dozen rooms of the MMFA’s West building. With conservatism rising again as the US enters another election and middle schoolers everywhere still clinging to Andrew Tate’s gospel, Marisol’s domestic life visions are as relevant as ever. But as her work shows, anything can be chipped away enough to create something beautiful.

Marisol: A Retrospective closed on January 20th. Look up her stuff online.

This is How You Smile

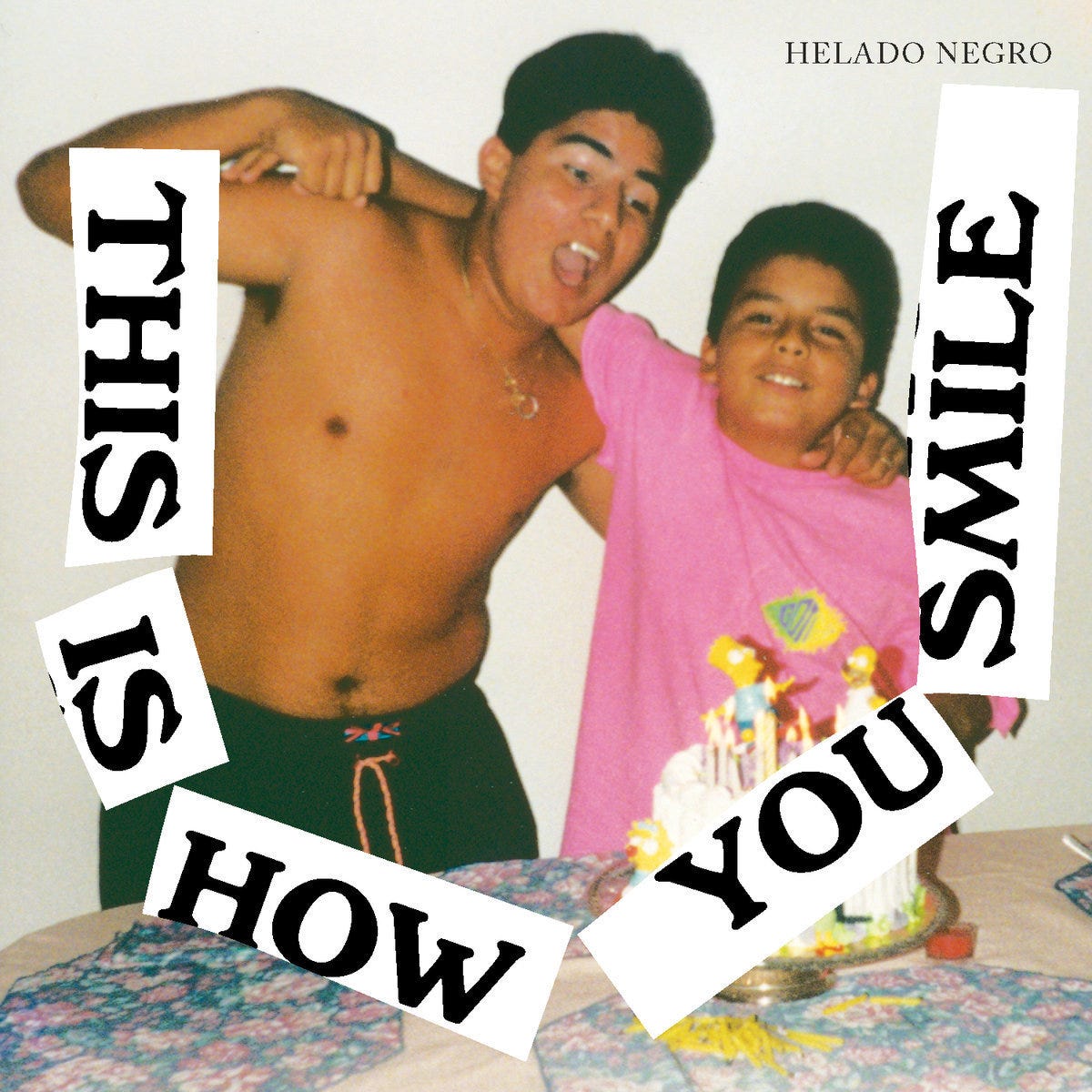

Any Latino who tells you that they don’t like The Simpsons is lying. Jokes hit different in the Spanish dub, with its speed giving more time for puns and references. There’s also something objectively funnier about the name “Homero” over “Homer.” Note: I am talking about the Latin American dub. The Spanish one can go kick rocas. But ask any brown kid who the coolest cartoon character is, and they’ll probably say Bart Simpson. The cover for This is How You Smile proves it, with a tiny Roberto Carlos Lange standing in front of his birthday cake alongside his brother. The album itself is equally warm and nostalgic, celebrating Lange’s heritage through light synth-folk jams and barrio ambiance.

“We’ll light / ourselves on fire / just to see / who really wants to believe,” Lange sings on the album’s opener, “Please Won’t Please.” It's the first step in his reminiscence of his experience of growing up Latin, dancing around the question of whether there’s anyone who really cares about us outside our own people. Synths and vibraphone dance with each other

Synths are dropped for acoustic guitar on “Imagining What to Do,” with the vibes still hanging in the background. Strings and piano accentuate the ends of phrases, punctuating Lange’s gentle delivery

“Echo for Campdown Curio” sees the first of the album’s ambient-esque pieces, with sandaled footsteps and monkey noises giving way to hums and vibraphone dings before static silence. A break from the finely composted tracks before it, it still maintains the album’s reflective nature. Here, the album switches to Spanish, as if Lange was heading home to Ecuador and the memories that come with it.

“Fantasma Vaga” sees the first full-length Spanish performance of This is How You Smile. Lange’s baritone voice is set atop a low whirring synth and gentle kicks. “Fantasma Vaga” (wandering ghost), he repeats before breaking things down midway through the track; the mid-song interlude is key to many tracks through Helado Negro’s discography. Almost always instrumental, it gives a break from Lange’s loose prose, resetting the vibe while emphasizing the subtle differences in the track’s second half. “Pais Nublado” does this, too, setting the tone for the English-Spanish duet on the peace and strength that only comes with relationships. Compressed percussion takes a backseat to lyrics; the driving beat is still there, but Langes’ poetry is the most important thing here. Unity between friends, instruments, and lovers is what Lange puts first.

This is How You Smile continues on this path of gentle synth-folk with Latin accents. “Seen My Aura” retains the same intimate approach, with borderline bachata beats as Lange sings of the closeness that gives life meaning. “Sabana De Luz” brings in steel drums on a gentle ballad for a perfect love. Sufjan Stevens pulls up to bring oscillating tones and fuzzed-out pianos on “November 7.” Each track sings to his experience as a Latin man and that of his community at large, bringing the expectations, relationships, and challenges of Latinidad forward in a carefully wrapped collection of sounds.

As the challenges facing an entire people may be inflated again, by an equally swollen man, Helado Negro is the guiding voice saying that things will be ok. He doesn’t despair on This is How You Smile, taking everything in stride as if he were just walking through his barrio with his buddles. Every Helado Negro project is such a treat, and This is How You Smile is the sweetest one yet.

With his latest album Phasor arriving soon, Helado Negro has again evolved. Its first single, “LFO (Lupes Finds Oliveros),” pays tribute to one of the most fascinating people in music history, Lupe Gomez. A factory worker for Fender during the 1950s, Gomez’s signature has become synonymous with technical excellence. The amps she wired have become highly sought after, with ornate wiring that can only be described as magical in quality. Helado Negro’s track bears the same feeling, with its psychedelic interlude and woozing guitars. The video, directed by Lange, acts as an extension of the track’s breezyness. If this, and the other singles serve as any indication, Phasor may be one of the year’s best albums.

This is How You Smile is available on all streaming platforms via Rvng Intl.